APOKATASTASIS: PART III

On Christ the Mystery

For the previous entries in this series see Part 1 and Part 2. During the writing of this article David Bentley Hart announced his Stanton Lectures titled “The Light of Tabor: Notes Towards a Monistic Christology,” but because of technical difficulties their public release was delayed slightly, the first of these becoming available to view recently after I had already finished this article and was in the process of editing. I have chosen to publish this article without recourse to the new lectures which are still being released. I hope I have not misrepresented Hart’s positions and I encourage everyone to watch his lectures as I will, the first three of which can be found here (Lecture 1), here (Lecture 2), and here in which his disagreements with Wood are expounded at length (Lecture 3).

INTRODUCTION

Jesus Christ is a mystery, the mystery of all mysteries, but what does this mean? Is Christ a mystery because the Incarnation is a special case restricted in its scope to the individual Jesus alone? Certainly not. Is he a mystery because the union of divinity and humanity in him is an exception alien to the nature of creation, something irrational and so influencing all else by an external and nihilistic compulsion? Not at all. From the Apostle Paul to Irenaeus and Origen, Gregory of Nyssa to Maximus the Confessor, Soloviev to Bulgakov, Christ has been understood as Mystery because in Christ Incarnate the nature of all reality from middle to end to beginning is revealed. Christ the God-man is the concrete reality of all things as being their principle as beginning and end:

Who verily was foreordained before the foundation of the world, but was manifest in these last times for you (1 Pe 1:20)…Who is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of every creature: For by him were all things created, that are in heaven, and that are in earth… all things were created by him, and for him: And he is before all things, and by him all things consist. And he is the head of the body, the church: who is the beginning, the firstborn from the dead; that in all things he might have the preeminence… having made peace through the blood of his cross, by him to reconcile all things unto himself; by him, I say, whether they be things in earth, or things in heaven (Col 1:15-20)… And when all things shall be subdued unto him, then shall the Son also himself be subject unto him that put all things under him, that God may be all in all (1 Cor 15:28).

The person referred to in all of these passages is Jesus Christ, the God-man in his fullness. That this is true is evident from the New Testament author’s ascribing of all these things to Jesus Christ, including preexistence and creation. In the post-apostolic period St. Irenaeus explicates this belief in brilliantly scandalous words, “Since he who saves already existed, it was necessary that he who would be saved should come into existence, that the One who saves should not exist in vain.”[1] The Nicene Creed canonizes this theological consciousness in its confession that we believe “In one Lord Jesus Christ… begotten of the Father before all ages… through whom all things were made,” and later theological elaborations translated this faith into the logic of the hypostatic union. The Son of God as Person is the composite hypostasis Christ because “not only is Christ out of these [two natures], but He is also in these, and what’s still more proper to say, He is these.”[2] There was never a time when Jesus Christ was not, because creation is Incarnation, Christ eternally being the union of divine nature with creation as His Body in his one Person, because “he is before all things… but was manifest in these last times for you.”

The above view of Christ as the mystery of all things, the Day Star that is all things and is the illumination of all thing’s true nature, requires a more thorough explication as a theological metaphysics. In attempting this explanation, I will be turning to the thought of Jordan Daniel Wood, David Bentley Hart, and Fr. Sergius Bulgakov, the foremost modern thinkers on the topic of Christological monism, which will require an engagement with their disagreements and an assessment of their positions. Through this engagement and assessment we will demonstrate that a proper Neo-Chalcedonian Christology reveals the Incarnation as predicated upon and manifesting the reality of apokatastasis, the salvation of all.

CHRISTOLOGICAL MONISM

In his doctoral thesis titled That Creation is Incarnation in Maximus Confessor, Jordan Daniel Wood argues persuasively that when St. Maximus says creation is the Word becoming “thick” or Incarnate as the logoi, when he makes statements of absolute identity between God and world in Christ, and when he says that the “mystery” of Christ is the working of the Incarnation in and as all things, he actually means it. In conveying Wood’s argument briefly, it is necessary to start with the fact that for St. Maximus the historical Incarnation is the revelation in time of the nature and beginning and end of creation because it is what effects and simply is the nature and beginning and end of all creation and creatures:

The mystery of the incarnation of the Lord is the key to all the arcane symbolism and typology in the Scriptures, and in addition gives us knowledge of created things, both visible and intelligible. He who apprehends the mystery of the cross and the burial apprehends the inward essences of created things, while he who is initiated into the inexpressible power of the resurrection apprehends the purpose for which God first established everything.[3]

The ”inward essences” of creation in the above translation are the logoi which are also the purpose or end of all creatures, and the logoi are nothing other than the Logos which, as St. Maximus says and Jordan Daniel Wood forcefully argues, is as Hypostasis the positive principle which precisely in assuming or enhypostatizing creation into his hypostatic identity generates the infinite natural difference between creation and divine nature.[4] St. Maximus’ cosmology, ontology, and eschatology is a thorough application of Neo-Chalcedonian Christo-logic to all of these things, that is, Wood argues that the logic of the Incarnation is the logic of creation. The Logos “is” all things in an absolute identity which does not jeopardize the distinction between divine nature and creatures because this hypostatic union is the very generation of their essential difference.

A key point for Jordan Daniel Wood’s interpretation of St. Maximus is his argument that according to St. Maximus the hypostatic union establishes fully real, essentially distinct natures, that are non-competing regarding wills and activities while having absolute identity, that is, hypostatic identity, such that Christ is not “more” God than man and the Saints in deification and all in the eschaton are equally divine with God. This maximalist view of deification is very clearly articulated by Maximus’ according to Wood’s translation:

For they say that God and man are paradigms of each other, so that as much as man, enabled by love, has divinized himself for God, to that same extent God is humanized for man by His love for mankind… Just to the extent that he contracted us for himself into union with himself, to that same extent he himself expanded his very self for us through the principle of condescension.[5]

The non-competing, fully free in self-determination, and yet completely aligned view of the relation between divine and human agency and activity is also not only explicit in St. Maximus’ theology of creation and creature’s existence as the logoi of the one Logos, but also in his defense of the Dyothelite doctrine through theological exegesis of Christ’s agony in the garden of Gethsemane. It is of central importance to St. Maximus’ defense of this doctrine that in Christ the human will was completely free from domination by the divine will or activity, that salvation was wrought by Christ as God and man as the properly free expression of the essential power of both natures, and thus that it is necessary to Orthodox Christology, at least in the case of Christ, that absolute freedom exists without potential to sin. But… isn’t that view of freedom simply the fact of how potentiality/activity must be understood according to the tradition of monotheism/monism that St. Maximus inherited and elaborated upon from St. Dionysius and past tradition? More to the point of Jordan Daniel Wood’s thesis, it is not possible to restrict anything to “the case of Christ,” because the mystery of Christ is the ontological foundation, principle and telos of all things. Thus, according to Wood, Christ is the mystery of all things as His hypostatic identity establishes the difference in identity of creation in and with God, meaning that creation only exists essentially (being ex nihilo, finite, developing, etc.,) distinct from divinity because of and as always being identical to the hypostasis of the Logos, and in existing essentially distinctly from divinity reveals His divinity through this difference, for Christ is from, is in, and is His two natures unconfusedly and indivisibly.

There are, however, some issues with this articulation of Christological monism. While Jordan Daniel Wood is a radically faithful expounder of St. Maximus thought, taking the Confessor’s shocking statements seriously rather than forcing them to be mere metaphor, I think his specific views on the essential non-relation of divine and human natures, only united through hypostasis as indifferent to nature, are too anachronistic to be Maximian and run up against serious metaphysical objections (when understood in ways with which Wood may or may not disagree).[6] In his thesis Wood explains his rejection of any principle of natural relation or commonality between divine nature and human nature in the hypostatic union, as follows:

The singular identity of hypostasis, the only positivity that exists for itself (hypostasis’s second definition), makes possible and actual the concrete union of my body and soul (first definition)—and because of hypostasis’s absolute indifference as the real identity of each, these natures, relieved of that burden (of achieving their own mutual identity), can preserve the universal principle that makes them what they are. The hypostasis itself is a mode of union that grants absolute identity to essentially different realities. Only here, only in this way, do they receive “identity with one another”… if creation’s logic is Christ’s, then there is never a question of essential or natural identity (or even relation) between God and world. Hypostatic logic completely relieves nature of that burden.[7]

The issue here is the understanding of hypostasis as completely “indifferent” to the natures it is, because what this term seems to convey is that hypostasis and nature/essence are not two distinct but inseparable and mutually conditioning aspects of being which only together are God or the human being, but rather are opposed principles, making it unclear how hypostasis and essence can manifest one another if they are so heterogeneous. This issue is exacerbated by its application to the Incarnation, in which Wood argues the “indifference” of hypostasis makes it capable of grounding the absolute identity of two infinitely different natures, which infinite difference he seems to insist goes beyond the difference of infinity and finitude.[8] While Wood does explain that “no hypostasis really exists except as possessing and therefore actualizing itself in a nature,”[9] this definition of the hypostasis as “en-essenced” simply highlights the problem. How does a hypostasis actualize itself in and as a nature if hypostasis is indifferent to nature, which would seem to erect an unbridgeable gulf between subject and content which precludes their living co-actuality, and how are two infinitely different natures then meant to be united in and convey the identity of this hypostasis?

Following from the above, the issue of making hypostasis into the sole reality or principle that bridges the divine-human divide and so is divine-human, denying this to nature, is that hypostasis and nature become opposites in a dualism of hypostatic divinity and natural createdness. The making of nature into the completely “unlike” divine nature, while making hypostasis of the same ecstatic reality as divine hypostasis, would in fact seem to make divine nature and human nature like one another (which Wood maintains they are not) in their shared heterogeneity to the ecstatic indifference of divine and human hypostases. While hypostasis and nature may operate by different logics, taking this too far can lead to a kind of dualism within the structure of being, and therefore I believe a Christological monism must conceive the union of divinity and humanity as equally natural and personal, preserving creation’s wholeness in an even more thoroughgoing monism.

A great supporter of Jordan Daniel Wood’s scholarship while also being an acute critic on the points mentioned above, is David Bentley Hart, whose own approach to Christological monism draws on the work of Fr. Sergius Bulgakov and his Sophiology in explicating the positive side of Chalcedon and the Neo-Chalcedonian tradition. In his essay “Masks, Chimaeras, and Portmanteaux: Sergii Bulgakov and the Metaphysics of the Person,” Hart explains that for Bulgakov the ontology of personhood is the structure of the hidden and the manifest, in which the subject’s infinite inner depth of content coinheres with its revelation in the objective other, the subject only constituting itself through this self-revelation of itself as the for-itself (subject becoming object) in and as another, this “as” or the “am” of “I am Thou” being the copula uniting subject and predicate in the ontological structure of personhood in which I (my unique depth of subjectivity) and the other (my objective revelation) “are” one (the actuality by which “we” only exist as living in one another and so constituting each other).[10]

This ontological structure is not restricted to hypostasis, it is the structure of all being as hypostaseity or hypostaticity, or of hypostasis’ relation to nature. Nature or essence grounds person or hypostasis just as much as the reverse is true because nature is the predicate of the hypostatic subject, and in this nature is emphatically not a static deposit. Nature or essence is the reality of living being, the fullness of content as dynamic principle to be actualized and more than that “longing” to be actualized. While person is the subject that uses their will, nature is the ground of this potentiality as itself being living will as Eros directed and inherently striving towards actualization and even ecstasis, and so hypostasis only is as the actuality of essence and essence is only as actuality of hypostasis, and the ecstasis of one is that of the other.[11] This is what Fr. Sergius Bulgakov means when he discusses nature as Sophia as the power to be hypostatized and to reveal hypostasis (hypostaticity),[12] and what David Bentley Hart succinctly summarizes in his critique of certain understandings of hypostatic union as achieved through enhypostatizing natures:

What could it possibly mean to say that “person” or “hypostasis” transcends nature, or is prior to nature, or (in the cases of the God-man and of deified human beings) is indifferent to the differences between the natures it instantiates? Surely, for this to be intelligible, one must also grant the reciprocal claim that any “personal” hypostatic realization of a nature is the realization of a nature that is intrinsically personally hypostatic—which is to say, capable of actuality only in and as “personhood,” whatever that means—and that this capacity, which clearly lies at the ground of both natures, is already an essential unity, and can in fact be no less a unity than is the full expression of that capacity in the one indivisible personhood of Christ… Only an intrinsic orientation toward personhood in the divine and human natures at once makes it possible for them to be fully actual in and as the same person, in such perfect unity that those natures are not merely juxtaposed, but truly coinherent one in the other.”[13]

In short, if we want to have a proper understanding of Christology to inform a Christological monism, we need to retain the understanding of hypostasis as the subsistence of a nature, and this yields an ontology in which “hypostasis and nature must remain the two indissoluble sides of a single metaphysical principle: as ontic actualization and ontological axiom.”[14] When this corrective is applied to Jordan Daniel Wood’s approach to the logic of creation as Incarnation, it allows us to retain the absolute difference between God’s infinity and creation’s finitude (while also affirming their absolute symmetry in Christ) while moving towards a more thorough monism in which the question of the Incarnation is that posed by Hart and Bulgakov, “how is it that a full subsistence of the divine nature and a full subsistence of the human nature can be one and the same subsistence, without contradiction?”[15] The answer Hart and Bulgakov give to their proposed question is that the Person of the Logos is the Hypostasis of all creation, in his particular and cosmic incarnation which are one and the same, because created nature bears the same principle of grounding and being actualized in divine personhood as the divine nature in its proper mode as unfolding of the infinite, such that the Incarnation of the Logos hypostatizing divine and human natures effects their perfect interpenetration and distinction because the Incarnation is precisely their natural fulfillment.[16] In short, the Incarnation is grounded in and reveals the primordial reality and principle of Godmanhood, Divine-humanity, Sophia, which is the reality of creation from beginning to end.

Summarizing all the above, a Christological monism and belief that creation is Incarnation leads us to the following affirmations. Creation is not something that God makes and then leaves to an uncertain destiny; creation is instead the eternally realized bringing into being of the divine-human Person of Christ in His fullness. Every creature, in a way that is not reductive of their own identity, is in its depths the Person of Christ, because to say that Christ assumes all things is to use the language of economy to convey the protological/eschatological reality that everything fundamentally is Christ. Finally, if we believe this then we must affirm that the end of all creatures (which is their beginning) is deified identity with Christ in the eternal day of the HaOlam HaBa, for “in that day shall there be one LORD, and his name one (Zech 14:9)” because the Lord is “the one divine Person who is all that is, who shall in the end be all in all, and who alone is forever the ‘I am that I am’ within every ‘I’ that is.”[17]

THE DIVINE-HUMANITY

While we have asserted that the above rendition of Christological monism leads to the necessary conclusion of Universalism, it is prudent for us to demonstrate this fact in a brief argument from the implications of the Dyothelite dogma. The doctrine of Dyothelitism is not simply an affirmation that Christ has two natural activities/wills, it is also the teaching that these two activities are non-competing (one does not overpower, restrict, or in any way impinge upon the other) and necessarily achieve according to their proper modes the same end which is, in the case of Christ, the achievement of the mystery of the Incarnation as the full actualization of these natures as being and manifesting the Logos, or to use Scriptural language, the perfecting of the Savior through sufferings resulting in the attainment of the name above all names (Heb 2:10, Phil 2:9-11). As St. Maximus, the champion of Dyothelitism, says:

You have demonstrated that with the duality of his natures there are two wills and two operations… and that he admits of no opposition between them, even though he maintains all the while the difference between the two natures from which, in which, and which he is by nature… This is why, considering both of the natures from which, in which, and of which his person was, he is acknowledged as able both to will and to effect our salvation. As God, he approved that salvation… as man, he became for the sake of that salvation obedient… [thus] He accomplished this great feat of the economy of salvation for our sake through the mystery of his incarnation.[18]

This said, we must also understand that while the working out of salvation as the full deification (and so incarnation) of Christ did admit of development in his earthly ministry (gradually revealing his glory and deifying nature), it is emphatically not the case that the full synergistic union of natures in their enhypostatized actuality (their full actuality as the Logos) is something that “could” not have been achieved. The Logos does not change in a temporal way from simple to composite hypostasis, as this would introduce temporal development into God and compromise immutability by changing His hypostasis. Rather, when we say that the Logos “became” a composite hypostasis we are simply articulating the ontological priority of divinity to creation using colloquial language. Using more precise language, we must say that the Logos is always eternally a divine-human hypostasis as He is eternally that Hypostasis of the Trinity enhypostatizing the eternal divine outpouring that is creation and so causing creation to subsist as Himself. Metaphysical precision regarding the logic of hypostatic identity is here indistinguishable from the Biblical insistence that Jesus of Nazareth is the Alpha and Omega (Rev 1:8).[19]

Thus, while the temporal frame of creation includes the perspective of successive development, in Christ’s earthly individual existence as well as in the development of his cosmic body, this temporal development is only as a manifestation of the ontologically prior reality (as final cause or end) of the complete actualization of created nature as His Hypostasis, or as all the logoi conformed to the Logos. Orthodox Christians would all admit (or at least should) that this argument is true in the case of Christ; there was no possibility that Christ could have failed in His humanity to be fully deified because who He is is the God-man, yet this deification was completely free, and so it is equally necessary to speak of this deification as the precondition for Incarnation as it is to affirm it as a result of the Incarnation. But again, there is no such thing as “in the case of Christ” as a mere individual. Christ’s Hypostatic identity from eternity as the subsistence of the natures He is is simply His identity as the whole of creation, every single being, and the logic of his individualized humanity’s relation to his Hypostasis holds true for all creation. Creation could not exist, which is the same as saying Christ could not be Incarnate, which is the same as rejecting the identity of the Logos as always Jesus Christ, without the absolute deification of all things being their precondition (which is consequently to say creation-is-Incarnation-is-deification).

By the power of this argument, we are compelled to affirm St. Gregory of Nyssa’s theological exegesis of 1 Corinthians 15:28 as simply and necessarily correct if we wish to continue affirming Orthodox Christology. Christ will be the fullness of Himself as who He is as God-man when His humanity, his body which is every single created being, is fully conformed to His person in freedom and so united to the Father.[20] And, indeed, the process of creation’s existence as movement from potency to act in its actualization towards or growth into “the measure of the stature of the fullness of Christ (Eph 4:13)” is itself the guarantee that this reality is always already accomplished in the Alpha and Omega as the fullness of divine-humanity.

CONCLUSION

In the beginning of this series I laid out the goals and scope of my arguments for Universalism, namely that I would argue for a Universalism which was metaphysically certain according to the best of Christian theological metaphysics, and so a Universalism rooted in an ontology of the human being which affirmed created freedom as self-determination and absoluteness in a non-competing synergy with God, and, finally, all of this would be grounded in and manifest by the Person of Jesus Christ, the Morningstar as the light of all being and rationality. Here at the end of this work, I believe I have adequately fulfilled all my promises. It is my hope that the Eastern Orthodox tradition, by itself and in dialogue with the rest of Christendom, comes to recognize the inseparability from and even equivalence of Universalism with the best of Christology, of philosophical theology, and of human freedom.

To conclude, a few song lyrics from a series dear to me. Let the reader understand:

You were looking without seeing

It’s not like you were blind

But something had you fleeing

From what you could find

Just hiding in plain sight:

You’re already always free

Now you’re looking and you’re seeing

Your every choice is fine

No plot limits your freedom

And the story line

Is yours for the making

The road less taken

Could be where you’re meant to be[21]

[1] Irenaeus, Against Heresies III.22.3.

[2] Jordan Daniel Wood, “That Creation is Incarnation in Maximus the Confessor.” PhD Thesis. (Boston College: https://dlib.bc.edu/islandora/object/bc-ir:108259, 2018), 65.

[3] Maximus, “First Century: 66” in The Philokalia: Volume 2. GEH Palmer, Philip Sherrard, Kallistos Ware, trans., eds. (London, UK: Faber and Faber Limited, 1990), 127.

[4] Wood, “That Creation is Incarnation,” 139.

[5] Maximus, Amb 10.9 and Amb 33.2 in “That Creation is Incarnation,” 22. To put this another way, the statement “God became man that man might become God,” if creation and incarnation are one reality, must mean that God is capable of becoming man because man is always already (ontologically) God-become, and conversely man is capable of becoming God because in his ontic depths mankind is precisely God-become-man.

[6] I wish to be clear here that I am not definitively claiming that Wood’s thought falls prey to these issues. There is still much work ongoing and to be done to clarify the relation or opposition, as the case may be, between the metaphysical perspectives of Hart and Wood. I am simply providing a tentative but informed assessment in service of a synthesis for my argument for universalism from Christology.

[7] Wood, “That Creation is Incarnation,” 58-59, 178.

[8] When positively explicating the difference between divine and created natures Wood does appeal to the difference between infinity and finitude, however this difference alone does not seem to be equal to the absolute difference he contends hypostatic identity alone with no natural commonality is the only answer for. Furthermore, David Bentley Hart’s own explanation of divine/created natural distinction as between infinite and finite has been a point of disagreement when Hart and Wood or one of his partners in thought have dialogued publicly. For example, see the comments between Hart and Wood here (a) and between Hart and Ty Monroe here (b).

[9] Wood, “That Creation is Incarnation,” 258

[10] David Bentley Hart, “Masks, Chimaeras, and Portmanteaux: Sergii Bulgakov and the Metaphysics of the Person” in Building the House of Wisdom: Sergii Bulgakov and Contemporary Theology. Barbara Hallensleben, Regula M. Zwahlen, Aristotle Papanikolaou, Pantelis Kalaitzidis, eds,. (Münster, GER: Aschendorff Verlag, 2024), 48-50, 60.

[11] This point is not an aberration introduced by Fr. Sergius Bulgakov, rather it is integral to the Neo-Chalcedonian view of nature defended by St. Maximus the Confessor. Natures are not merely collections of properties or static ontological categories, they are integral content in activity or motion (the natural will or energy), and therefore to assume humanity according to Orthodox dogma has meant the assumption of a living nature.

[12] See Brandon Gallaher and Irina Kukota, “Protopresbyter Sergii Bulgakov: Hypostasis and Hypostaticity: Scholia to the Unfading Light,” St Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly, 49:1-2 (2005), 5-46. https://www.academia.edu/220403/Protopresbyter_Sergii_Bulgakov_Hypostasis_and_Hypostaticity_Scholia_to_the_Unfading_Light_St_Vladimir_s_Theological_Quarterly_49_1_2_2005_5_46.

[13] Hart, “Masks, Chimaeras, and Portmanteaux,” 52.

[14] Ibid, 54.

[15] Ibid, 54.

[16] Ibid, 59.

[17] Ibid, 62.

[18] Maximus, Opusc 6 in On the Cosmic Mystery of Jesus Christ. Translated by Paul M. Blowers and Robert Louis Wilken (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2003), 173-175-176.

[19] By affirming this I do not mean to deny that the literal sense of, say, the Johannine prologue, is of a divine being descending through the heavens to earth. I am instead arguing that biblical symbolism/myth and philosophical theology dovetail in a necessary articulation of eternal divine-humanity. I also do not mean to imply that such a view limits theology to a Christological definition of God in opposition to and exclusive of all other religions and divine embodiments. I would in fact argue for the opposite, but that discussion is for another time.

[20] See Gregory of Nyssa, “In illud: Tunc et ipse filius” Eclectic Orthodoxy, October 4, 2019. https://afkimel.wordpress.com/2019/10/04/in-illud-tunc-et-ipse-filius/.

[21] “Road Less Taken,” Track 1 on Persona Q2: New Cinema Labrinth Original Soundtrack, Atlus. https://genius.com/Atsushi-kitajoh-road-less-taken-lyrics.

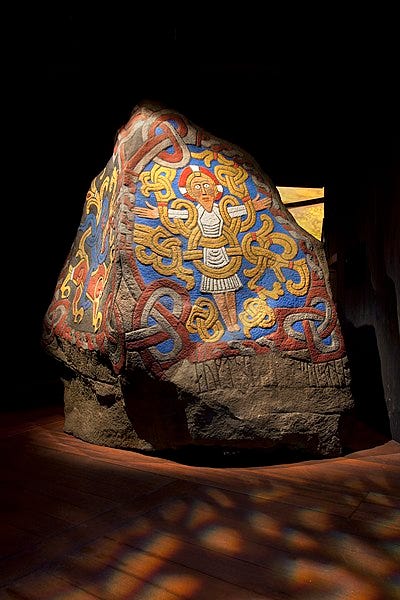

Really great read! I love to see the Mystery get some air-time, especially with human freedom as a point of focus! The idea of fate/destiny/lifecourses as eternally realized also strikes a chord. By the way, did you know Danish citizens all have that Jelling-Jesus on our passports? There's actually quite a lot of fun/spacy syncretistic stuff going on in late-viking age Scandinavian Jesus-imagery and mythology of gods like Odin or Thor!

So leaving Vespers now and I think you might think that I missed the whole point of your article being that in the Incarnation which for us took place at a certain time in history, but in reality was and is the beginning and the end as it was as well as everything to do with Christ, is our being and becoming. So sort of as an acorn is always going to grow into an Oak tree no matter what it does it was made to be an Oak tree so too we being made in the Image and Likeness of God that is our destiny……