Except it Die

A Meditation for Holy Friday

Alas for that man by whom the Son of Man is handed over; it would have been a good thing for that man had he not been born… Then Judas, the one who betrayed him, seeing that he had been condemned, changed his heart… and going away he hanged himself. – Matthew 26:24, 27:3-5[1]

Ridiculous man, what you sow is not made alive unless it dies. – 1 Corinthians 15:36

Fr. Sergius Bulgakov wrote an essay in 1931, between the publishing of his little and greater trilogies on Holy Wisdom, titled Judas Iscariot – Apostle-Betrayer. Split into three sections this essay re-envisions the personality, theological significance and historical archetype of Judas, beginning from and arguing for the fact that Judas was chosen by Christ as an Apostle, pre-eternally and in time, because Christ truly loved Judas. From this fact Bulgakov goes on to transform our image of Judas, taking the witness of all the Gospels into account, not to exonerate him but to shed light on the true nature of his sin, its relevance for us, and how it illuminates the question of how to conceive divine providence. Specifically though, in the conclusion of this essay Bulgakov is clear that his evaluation of Judas was inspired by seeing the Apostle-Betrayer as an archetype of Russia’s apostasy from Christ under the Bolshevik yoke.

The tragedy of the apostle-betrayer, his terrible fate, now stands insistently before us, because it has become our own fate, not personal, but national. For our nation, the bearer and defender of “Holy Rus’”, guardian of the brightly shining city of God, intelligible Kitezh, has now taken the place of Judas, the apostle-betrayer… What has happened and what is happening to Russia? Wrestling agonizingly with this unanswerable question, you involuntarily begin to scrutinize the terrible gospel image of the apostle-betrayer, and in its mystery you seek solutions to our own particular fate. This is how the problem of Judas, which had never been silent in our hearts, welled up again.[2]

This perspective is evident throughout the work as Judas’ (the red star) relationship to money and zealotry is interpreted through the lens of Socialist messianism, in the case of Judas and the Bolsheviks their views being characterized as containing truth and even love for Christ while at the same time being linked to the temptation of bringing about eschatological change through dehumanizing force. Where Judas, according to Bulgakov, betrayed Christ to force Jesus to bring the kingdom of God by force, only to be driven to suicide when he comprehended that the innocent lamb was to be slaughtered but could not comprehend that this death was true victory, the Bolsheviks were betraying the Church and Christian soul of Russia because it was seen as impeding the eschaton. While Bulgakov would argue for Judas’ salvation in another work (Two Chosen Ones: John and Judas), it is clear his ideas tended this way in this essay for the simple reason that Bulgakov foresees the salvation of Russia itself: “It is happening now, Christ is rising in Russia.”

Now, the above is not meant to merely summarize Bulgakov’s book, which is short and a must read if you are able (very relevant to our times), it is instead meant to introduce ideas for expansion and critique. Regarding criticism, while Bulgakov does admit that Christian history is itself full of examples of Judas-ness in how the Church has grown and formed itself, and that Christians must accept and seriously wrestle with the critiques of their history made by secular opponents, there is still present that familiar Christian reticence to judge itself with the same measure by which it judges others or its persecutors. The temptation of coercive power “has always held sway even in the ‘Russian Christian empire’ with its inherited fear of freedom,” but Bulgakov qualifies, “However, then it was more a sin of weakness than a religious temptation, and only now has it grown into a conscious ideology of ‘dictatorship’, i.e. coercion as such.” This qualification is dubious, as the Russian Church and Empire were the Church and Empire of the Josephites (Possessors) and eschatologically charged Raskol persecutions, the union of Orthodoxy with Autocracy as in the motto of Tsar Nicholas I, the abolishment of Patriarchates, the censorship of Church publishing by the government, violence directed against the Imiaslavie movement, anti-Jewish pogroms, brutal political repression and violent suppression of protest including the massacre of Bloody Sunday, the list goes on. One may contend that the difference in scale and national suffocation of freedom was far greater under the Bolshevik’s and therefore such qualifications are admissible, and perhaps that is correct, but the fact remains that for most Christian thinkers the Church retains superiority of perspective and so escapes being labeled Judas.

Expanding Bulgakov’s use of Judas to fit the revelations of our time, then, requires this identification of institutional Christianity with the Archetype of Judas. Bulgakov’s hopes for Russian revival have been frustrated precisely because the Russian Church has completely identified itself with coercive power, not out of weakness but out of willful self-definition, and meanwhile the opponents of the Russian Church defile themselves as well, invoking Constantine to bless tyranny in the West.[3] The same is true for most of Western Christianity which, if it is not silent in the face of these evils, is enthusiastically identifying itself with the rise of global nationalist and fascist power and nostalgia. Like Bulgakov in 1931 we are confronted by the presence of Judas and his fate anew, and in it we “involuntarily begin to scrutinize the terrible gospel image of the apostle-betrayer, and in its mystery… seek solutions to our own particular fate.” If Bulgakov’s writings, as well as the writings of many Orthodox writers of the early 20th century, should shame us in how they identify the evils of Nationalism that plague us today, then we also need to hear and even move forward with their criticism by applying it not only to those forces that try to mold the Church in their image, but to the Church as a historical reality itself.

I have chosen the Scripture pericopes heading this essay for the above-mentioned purpose. The historical and institutional Church has been quick to identify itself with the body of Christ, especially in its martyrs whose deaths are passages to life, emphasizing the Church’s victory over death. But if this is the reality of the Church as it really is, that is eschatologically, then it only appears in glimpses through the martyrs, unmercenaries, and righteous souls, those who were often “impoverished, afflicted, maltreated, they of whom the cosmos was not worthy (Heb 11:37-38),” and often they were treated this way by the unworthy Church of history. Indeed, the Church of history cannot be identified absolutely with the eschatological Church because, unlike Christ and the martyrs whose deaths are swallowed up in life, the historical Church must die and die continually in striving to become perfect and manifest the life of the age to come. Crucially, this ecclesial dying is not reducible to the individual dying daily of the penitent Christian, it must be the corporate dying of the corporate sinful form, that is, the Church must repent of its historical and corporate sins, those historical accretions it has come to identify with so strongly (especially worship of and identification with power, clericalism, love of money and favoritism towards the rich, enforcement of schisms, persecution and censorship, etc.).

Bulgakov says in his work Unfading Light, addressing the question of the growth of God’s kingdom in history, “it is a shortsighted error to think that simply in virtue of ‘evolution’… the good will be strengthened in humanity… as if automatically… only evil accumulates in that way, while good is only realized in the world by free spiritual struggle.”[4] In other words, while the simple force of historical inertia can preserve communal habits and customs, it cannot preserve truth, truth is only preserved by continual critical engagement with life. This is why, as David Bentley Hart argues, traditionalisms are always based on sickly nostalgia, inevitably fetishizing a form from recent memory packaged as the eternal truth, or in the case of traditionalist converts a simplified polemical version of their new faith is constructed based on all the same concerns and ideas brought from their former disappointing life.[5] Unreflective reception of the past leads to unthinking ideology in the present, and these can only be combatted by critical, repentant reception of the past in service of a better future. This is true tradition and inevitably requires relinquishing the historical Church’s privilege of perspective and right to benefit of the doubt, especially concerning claims of infallibility or unquestionable authority which are nothing but “ideological and institutional myth.”[6]

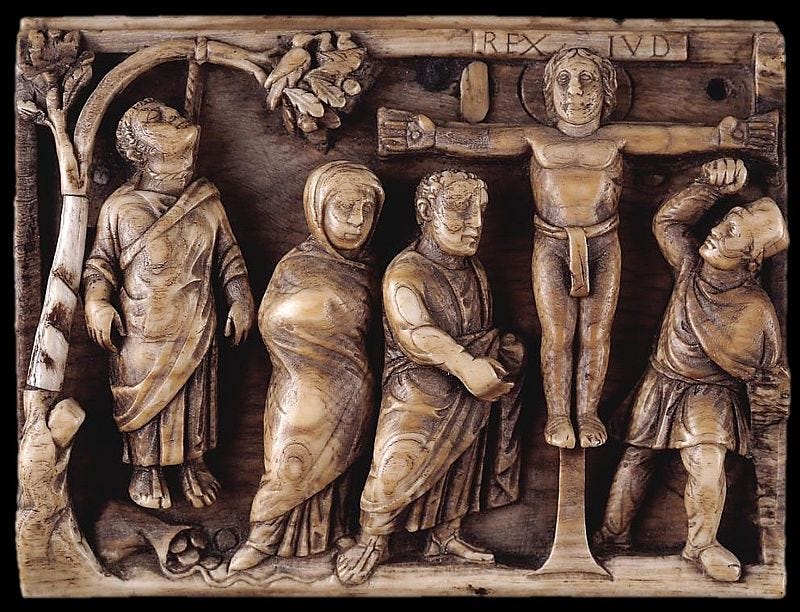

The above said, of the two hanging upon a tree during Holy Week, the historical Church finds its example and archetype just as much in the Suicide as in the Crucified. With Judas then the Church in history must recognize its sin, change its heart, and hang upon the tree continually, dying to itself so that it may be raised by Christ, otherwise it not only will not but does not live. It is only by doing so that the historical Church can become a force in history for the gradual realization of the kingdom of God, indeed, it is only those moments when the Church dies to itself which will be counted as life in the eschaton, all the rest will be subject to the condemnation “it would be good had it not been born.” Therefore, the Church requires a belief in the apokatastasis of all to justify its own existence, for it is the Apostle-Betrayer par excellence. The Orthodox Church, and Christianity in general, must not interpret Christ’s words to Judas as meaning “it were better you were not born because you will be eternally damned,” rather Christ’s meaning must be understood as follows, “my beloved, it were better you had not been born into this wicked world whose Archon has twisted your love, but I will save you through death as I trample down death by death.” It is only this interpretation, this hope, that can ensure Christianity that Christ will not abandon it, though what form the Church will eventually take is not known except that eventually, perhaps only beyond the bounds of history, it will be the form of Christ (1 Jn 3:2-3).

[1] All Scripture passages are from the David Bentley Hart, The New Testament: A Translation 2nd Ed.

[2] Citations are from the kindle edition and can be found by word-searching.

[3] For info on the Moscow Patriarchate’s depravity see my previous article here (1). For Archb. Elpidophoros’ comparison of Trump to Constantine see here (2).

[4] Fr. Sergius Bulgakov, Unfading Light: Contemplations and Speculations. Translated by Thomas Allan Smith. (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2012), 350-351.

[5] David Bentley Hart, Tradition and Apocalypse: An Essay on the Future of Christian Belief. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2022), 13-16.

[6] Ibid, 173.

This is a very thought provoking article, and a great read.

In regard to your statement that Christ's words should be interpreted as, “my beloved, it were better you had not been born into this wicked world whose Archon has twisted your love, but I will save you through death as I trample down death by death", I would revise them just a bit to read, “my beloved, it would have been better if you had merely been stillborn rather than to have been born into this wicked world whose Archon has twisted your love, but I will save you through death as I trample down death by death.”

In much of Christendom, Christ's words are understood to mean Judas must be damned for all eternity, and that universalism is therefore a heresy, as if universalism is true and Judas will one day ultimately be saved by the Christ who died to truly defeat death, hell and the devil for every creature, no matter what evil he did or experienced, it would certainly not have been better for him to have never been born, since he will ultimately experience never-ending bliss.

However, if the proper interpretation is, “my beloved, it would have been better if you had merely been stillborn rather than to have been born into this wicked world whose Archon has twisted your love, but I will save you through death as I trample down death by death", universalism can still be defended and held to, as a stillborn babe will also experience never-ending bliss, yet without ever doing wilfully evil, let alone selling their own loving Creator for 30 pieces of silver, as Judas did.

May God have mercy on ALL, and may we ALL always remember that God loves even those we consider "evil", far more than we could ever even love ourselves.

Dear Noah, I'm a french journalist writing about faith and spirituality. I'm writing now an article about conversions to orthodoxy for L ADN magazine. After reading your oieces about “orthobros”, I would like to interview you. Can I contact you by mail or you at marcbonomelli@gmail.com ? Your help would be very insightful!