On Empathy, Reason and Rebellion

While yet a child,

And ignorant of life,

I turned my wandering gaze

Up toward the sun, as if with him

There were an ear to hear my wailings,

A heart, like mine,

To feel compassion for distress.

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Prometheus

Empathy is the Devil’s passion, the lion roaming to seek who it may devour, prowling outside the door of the heart waiting for it to open and so to strike, to bleed that already bleeding heart until dead and damned. At least, this is how empathy is often characterized today. Whether it be the plight of migrants being stripped of rights and torn from families because they violated lines on a map, women feeling the call to ordination, or the homosexual loving a partner of the same sex, to feel empathy for these people is to sully oneself with their sinful condition and fall pray to the lure of caring and acceptance. Do not feel, do not empathize, do not betray God.

Of course, the majority who support bigotry towards such people and circumstances would object to being characterized in this way. Isn’t it true, after all, that it is not empathetic to a drunkard to encourage his drinking, and aren’t there many other such examples of this kind where the only loving response is to condemn the evil to save the sinner? Certainly this is true and no one can deny it, but appeals to this truth are hollow because the reason an addiction to drink is wrong is known through the movement of reason which, entering into the experience of human life and discerning what is good for the human being, emerges with a judgement that addiction is an evil because it is contrary to the good of the human being. To be a person is to be rationally free, meaning rationally realizing the ends of person as a unique subject of love in communion, and as addiction enslaves the person to a debilitating solipsism it is therefore evil. In short, it is an internal judgement inherently springing from the reality of the person itself, not an external imposition reducing the human to a piano key played by brute symbolic forces.

It is just this kind of reasoned judgement that is disallowed by the bigot in condemning empathy, but as this process and conclusion of reason is simply the nature of reason itself, thus revealing that the ecstatic nature of reason is equivalent to sympathy or empathy, the bigot is inherently irrational. Take for example the usual response to women who feel the call to ordination, “there are plenty of other roles in the Church for you.” Whereas a man is counselled to listen to the call of the spirit to discern the priesthood a woman is denied the ability to witness to this call and so ipso facto is denied an inner life and experience, and often also told that this is justified by completely impersonal reasons couched in arbitrary symbolism, as if symbolism cannot be used to justify almost anything. The same is true of the homosexual whose ecstatic love is no different in any essential way from that of the heterosexual, and which cannot be condemned by appeal to a puerile understanding of natural law if one is of a proper personalist tradition.[1] Likewise, the undocumented immigrant is considered subject to the inhuman violence of separation and deportation for purely externalist reasons, as if the inherent rights of human dignity should be subject to brute law.

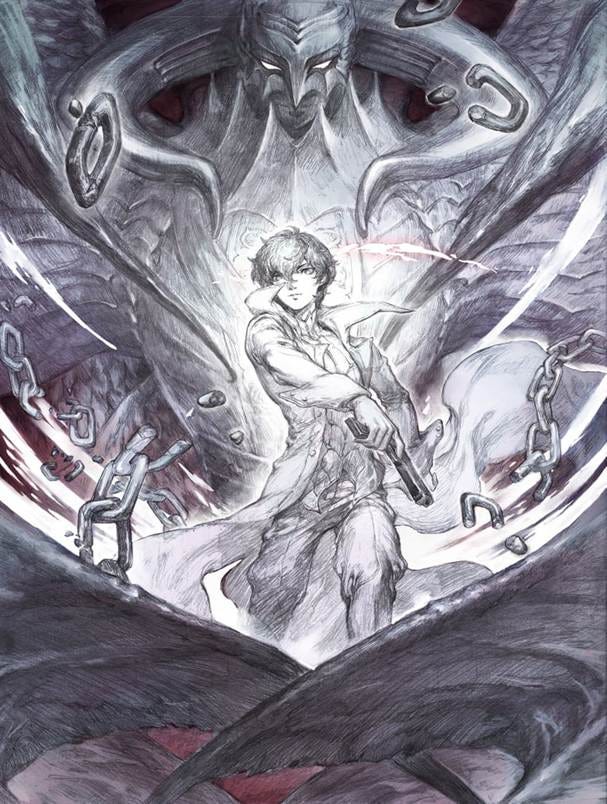

My argument may again be objected against because I have grouped the above three issues together, as two are traditionally considered sin while the other is only sometimes thought to be, but I have grouped them thus because they especially represent the three key restrictions of empathy and reason making up the Christian nationalist mindset: Misogyny, such that the male perspective alone can have agency and judge social value; Normative prejudice, such that the minority for no other reason than being a witness to the insufficiency of the norm are to be denied agency and perspective; Limitation of empathy, such that in general empathy can only be extended so far and therefore it is simply natural for their to be a swathe of humanity, the margins, subject to indifference at best and hate at worst. One may assess and classify such things in other ways and categories but, regardless, this should suffice to illustrate the nature of Christian nationalism (or neo-traditionalisms in general) as an inherently irrational worship of power invested with a certain character that inevitably takes the form of the tyrannical patriarchal Archon of biblical literalist inerrantism. A God no different than the wrathful tormenter of Prometheus, “shackling him in adamantine chains that will not break… so he will learn to bear the rule of Zeus and end that love he has for humankind.”[2]

Surely I would speak to the Almighty, and I desire to reason with God… O that ye would altogether hold your peace! and it should be your wisdom. Hear now my reasoning, and hearken to the pleadings of my lips. Will ye speak wickedly for God? and talk deceitfully for him? Will ye accept his person? will ye contend for God?... He will surely reprove you, if ye do secretly accept persons. – Job 13:3-10

There are many ways to tackle the issue of Biblical literalism and inerrantism, some boring and often useless such as providing contradictions of numbers or events in the text which an apologist will wave away by any explanation no matter how unlikely, and others more important and edifying, namely demonstrating that theological reading is inherently a de-literalizing and critical reading of the Scriptural texts. In Dionysius the Areopagite’s Letter IX he unequivocally rejects as literal and historical every moral portrayal, metaphysical description, and action or command attributed to God that is unacceptable to reason, arguing they all must be allegorized in the vein of Neoplatonic exegesis, and further clarifying:

… All this is to enable the one capable of seeing the beauty hidden within these images to find that they are truly mysterious, appropriate to God, and filled with a great theological light… This is so in order that the most sacred things are not easily handled by the profane but are revealed instead to the real lovers of holiness. Only these latter know how to pack away the workings of childish imagination regarding the sacred symbols.[3]

Following this patristic wisdom let us so examine, for example, the origin and problem of evil as it is understood by Christianity popularly. The popular and literalist understanding is that a man and woman in a garden ate a fruit (or grasped at immortality) they weren’t supposed to (or that they took it in egoism before their time) and God condemned them and all life then and after to an existence of suffering and death outside of Paradise. In historical context the tale in Genesis of course says no such thing, but even simply granting what the story reads as within later tradition a literal understanding is unacceptable. Is God so incompetent as to hinge the reality of universal suffering on the choice of two creatures, who are somehow rigged like a bomb to spread death genetically or cosmically? Worse, can we honestly worship a God who condemns a child to starvation because of millennia old sins? Can suffering and death have a reason or cause at all, and if not, how can we accept the many biblical portrayals of suffering and death on individual and mass scales being the just exchange for wrongdoing (or simply otherness), let alone the ravings of Christian leaders today claiming a hurricane is a punishment for society being too secular, the slaughter of Ukraine is justified because they have pride parades, or that Palestine must be put to genocide so God can bring the end times?

Grappling with the problem of evil himself, the philosopher and theologian Semyon L. Frank, a Jewish convert to Eastern Orthodoxy who lived through the horrors of the Bolshevik Revolution and WWII, argued the following:

To “explain” evil would be to “ground” it and therefore to “justify” it. But this contradicts the very essence of evil as that which is illegitimate, as that which should not be. Thus, any solution of the problem of theodicy is a conscious or unconscious denial that evil is evil… The only legitimate attitude toward evil is to reject it… not to explain and thus to legitimize… [Therefore] If we consider the biblical tale of Adam’s fall (and the fall with or in him of all of mankind or all creatures) to be only a “myth,” a depiction of something in the form of a temporal event which by its nature could not have occurred in time… then we can say that the fall of the world is not a theological dogma and not a metaphysical “theory” or “hypothesis” by which one can “explain” the appearance of evil in the world, but rather a simple statement or phenomenological description of the state of the world’s being.[4]

Considering this truth, we must recognize that it is the examples of Abraham, Jacob, Moses, the various Prophets and especially the book of Job, who really matter in revealing to us the proper existential and theological relation of man to God in the face of suffering, death, and creation’s phenomenological ambiguity. That is, the human person must never be an “accepter of persons” in regard to God, never treat God as a voluntaristic will who is right because he is might, but instead must reason with God, which is to say, must recognize that God is the Good which is Reason itself and so is empathy and love itself, that God is identical to the deepest truth of each thing and never a brute fact closing off reason. The God sought and discovered in this way is the infinite God and non-other, transcendent and containing all things and the ever-receding yet ever immovable horizon of infinite being. Thus, the theologian Job appears blasphemous to his false friends in their infantile piety when his rational and righteous indignation declares that there is no justice in his sufferings, and just so these ignorants are equally bewildered when he declares “He also shall be my salvation: for an hypocrite shall not come before him (Job 13:16),” for what is impiety to them is the greatest theological piety affirming that God is not a being among beings, a ruler exercising lordship, a tyrant, but that God as the greatest is the servant (Mtt 20:25-28).

Rabbi Eliezer then said to them: If the halakha is in accordance with my opinion, Heaven will prove it. A Divine Voice emerged from Heaven and said: Why are you differing with Rabbi Eliezer, as the halakha is in accordance with his opinion in every place that he expresses an opinion? Rabbi Yehoshua stood on his feet and said: It is written: “It is not in heaven.” … The Holy One, Blessed be He, smiled and said: My children have triumphed over Me; My children have triumphed over Me. - Bava Metzia 59b.4-5

Dogma in the Orthodox Tradition is not meant to be and cannot be a limiter to theological reflection. Not only do its minimalist creedal formulations merely suffice as grammatical guide points for further thought, across the centuries the Orthodoxy and formula of prior periods is often necessarily replaced by new formulations and understandings. These may be outworkings of previous Orthodoxy to varying degrees (and one must remember that almost anything can be called implicit in tradition in hindsight) but just as often they repudiate the past. If in the case of dogma reason is never bound by bare authority, in the case of moral judgements this is even more clearly true. Always not only the theologian, but any person who is confronted with the reality of differing human experience, must declare that the truth “is not in heaven,” that is, not a brute fact or given of some revelation, and therefore revelation of the truth is found in the ecstatic act of empathy/reason.

The above said, tradition’s unity is found in its reality as a shared dialogue whose truth shines from an eschatological horizon which we struggle towards through constant wrestling with the Angel embodying our tradition. It is Jacobian struggle that constitutes the truly moral life, not an Inquisitor’s certainty. Thus, the neo-traditionalist mindset and that characteristic of the majority who make up the Right-Wing nationalist resurgence around the Orthodox Church and Christianity in general today, based as it is on a craven desire for a Holy Grail to cling to for safety and certainty, is inherently anti-traditional. Insofar as tradition is a living thing it is antithetical to the idea of giving up one’s natural duty of reasoning and judging, judging not only men but angels and God. It is only those in the mold of Job for whom God is not an idol, not reduced to concepts and psychological complexes, but is instead the infinite.

The Scriptures say, “rebellion is as the sin of witchcraft, and stubbornness is as iniquity and idolatry (1 Sam 15:23),” but of course this quote comes from a tale in which a king is punished for not completing the genocide of a people for a centuries past sin. It is true that rebelling against the truth is equivalent to idolatry because such rebellion is irrationality, but as often as not the majority position in Christian culture is that of irrational idolatry and the only answer is holy rebellion, to identify with God as the confounding darkness which is also always revelatory light. To quote S.L. Frank slightly out of context:

… insofar as it is, evil is also good… Every singular existent is not only an existent but also an existent “not.” Precisely this “not” as an element of reality in everything that exists makes up the deepest essence of what we call freedom. The immediate meaning, emanating from the ultimate depths, of this “not” and of “freedom” consists not in limitation, separation, diminution, but rather in an individualization which is simultaneously a transcending through everything that is limited and positive; an individualization which is the capacity to have also that (or to be also that) which the given singular thing, as such, is actually not… or, more precisely, we have our center inside ourselves precisely because this “inside” has its point of reference outside itself, in its connection with everything, in total unity.[5]

Evil is banal non-being, but that which is thought to be evil, pictured under the aesthetics of the dark, may be good, may be the revelation of the Good as the coincidence of opposites in rebellion against a false and myopic image of the Good which reduces the human person to a gear in the machine or a vessel for impersonal realities, chaining them to the mechanical law of identity (A = A). A Christian humanist rebellion against such false images and false Gods, in empathy reasoning through the infinite potentials and experiences of human being, is the only acceptable and actual continuation of tradition. Or, as St. Pavel Florensky writes:

… Prometheus, the Titans and all the other heroes who rebelled against God in the name of Truth and Goodness—these heroes become infinitely dear to all those illuminated with the ‘Light of Christ’ and blessed by the “Good News.” This apparent rebellion against God is revealed before healed eyes to be the bearing of God in oneself…[6]

All the above said, if nothing else, do not fear or revile empathy. God is the lover of mankind, or He is not God at all.

[1] See Dr. Aristotle Papanikolau’s “Orthodox Morality” on Sex or an Ethics of Sex?, Public Orthodoxy, November 4-6, 2019. Part 1 & Part 2.

[2] Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound. Translated by Ian Johnston. (Nanaimo, BC: Vancouver Island University, 2012). https://johnstoniatexts.x10host.com/aeschylus/prometheusboundhtml.html.

[3] Dionyius the Areopagite, Pseudo-Dionysius: The Complete Works (Classics of Western Spirituality). Translation by Colm Luibheid and Paul Rorem. (Mahwah, NY: Paulist Press, 1987), 283. I was reminded of this passage which years ago I had overlooked regarding its significance, by its citation in the comments of this article by Jeremiah Carey, along with other patristic quotes on the same topic.

[4] S.L. Frank, The Unknowable: An Ontological Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion. Translated by Boris Jakim. (Brooklyn, NY: Angelico Press, 2020), 279, 285. Bracketed mine.

[5] Frank, The Unknowable, 281-282.

[6] Pavel Florensky, Early Religious Writings 1903-1909. Translated by Boris Jakim. (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2017), 121.

I remember being baffled by the pseudo-controversy around empathy a few weeks ago. I did a bit of googling and found a more-conservative Christian willing to actually make an argument on the subject. Basically, his position was that sympathy was good, while empathy was bad. He took the latter to mean more than simply recognizing another's suffering. Under his definition, empathy involves actually abandoning one's principles in order to more fully identify with the other person.

But it seems to me that no one actually uses the word this way; even if we want to differentiate empathy from sympathy by saying that empathy is more radical in its identification with the other than sympathy, I still don't know anyone who would argue that you have to abandon your own values to empathize.

This is one of those cases where subtlety is required: on the one hand, I agree that if empathy required us to abandon our own values, that would be bad. But on the other hand, I don't think anyone actually uses the term this way. So this whole presentation of empathy as dangerous is built on a slippery bait-and-switch.

Riveting in its timeliness, this piece is undeniably poignant and expertly written. I shall be sharing it at once with others, and I suspect a great many people will be as scandalized by its content as by their inability to logically refute it.

"I am the way, the truth, and the life." Truth, it seems, to many people was spoken silently.

Love you brother. Godspeed.