Then said he unto them, Therefore every scribe which is instructed unto the kingdom of heaven is like unto a man that is an householder, which bringeth forth out of his treasure things new and old. – Matthew 13:52

The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goeth: so is every one that is born of the Spirit. – John 3:8

INTRODUCTION

Recently on Substack several authors have put forward articles and series of articles grappling with the problem of tradition and ecclesial identity as the outgrowth or self-understanding of such tradition, to proffer a Reform Catholic response which offers a “thick identity” for Reform Catholicism not only able to compete with conservative traditionalisms but also provide a clearly superior understanding of tradition’s past, its present lived reality, and its potentials for the future. Dr. Timothy Troutner put forward an article arguing for the end of the settlement in Catholic theology between the Ressourcement or Nouvelle Theologie and Neo-Thomism, compelling a thorough reassessment of the narratives and categories according to which modern Catholic theology has constructed its acceptable “orthodoxy,”[1] and Andrew Kuiper added to this seeking to expand these insights.[2] Dr. Jordan Daniel Wood and David Armstrong also, in a multi-part series, provided a vision of a “thick” Reform Catholic identity as a moving forward with the vision of Reform Catholicism born especially from Renaissance Christian Humanism and traced through Vatican II to today.[3]

As an Eastern Orthodox reader, I have found all the above writing to be ecumenically heartening and to constitute a challenge for Orthodoxy. Ecumenically heartening because the understanding of tradition and ecclesial identity expounded in the above projects, to my eyes, constitutes a Catholic adoption and creative elaboration of the understanding of the ecclesial that Orthodox theologians articulated and brought to the ecumenical sphere in the late 19th through 20th centuries, namely Church and tradition as Sobornost. To be clear, Reform Catholics are drawing on conciliar resources within Western tradition, not only on the fruits of ecumenical dialogue with the East, and this means Orthodox should both learn from Reform Catholics’ scholarship and ecumenically aid them in steering the Catholic Church towards this better future (something Dr. Wood and Armstrong argue as well).

Eastern Orthodoxy is challenged by the Reform Catholic project, however, because of its own failure to follow the similar visions of its theologians articulated in the past two centuries. While it was common for Orthodox in the 19th-20th centuries to construe their sobornost ecclesiology as the opposite of Latin authoritarian traditionalism, Nikolai Berdyaev rightly noted that Orthodoxy’s ideal was consistently betrayed by concrete reality, and so he asked:

It has become time already, when it is necessary to stop with the double-talk and back-biting and to give a straight-forward and clear answer, does the Orthodox Church recognize freedom of thought and of conscience? Is it equitably just on the part of the Orthodox constantly to accuse the Catholics, that they have no freedom, an accusation, based on the premise, that with the Orthodox themselves there is this freedom.[4]

This challenging question continues to ring today, because as an institution the Orthodox hierarchy has often shown itself to be a friend of authoritarianism, whether by supporting oppressive governments and political ideologies, or insistence upon clericalist traditionalism thwarting conscience and denying development in principle. An easy or plausible way of overcoming the national divisions and ecclesial politicking of our jurisdictions does not present itself, let alone the possibility of uniting under a forward-thinking theological vision and course of action to transform the world. Reunion with Rome is certainly desirable, but to think it would resolve our problems is naïve. Thus, it falls to the Orthodox person to continue the development of its reformist tradition in their own thought and actions, hoping that the institution will follow in time. However, insofar as this reformist tradition enlarges one’s vision beyond the confines of institution and encourages one to see unlimited truth and beauty in man and world, one can hope the consolation prize of institutional favor is not needed for satisfaction.

That is what I will be doing in this two part series, trying to articulate the hope of my religious vision, my fantasy. The perspective and arguments I provide, often drawing on resources in the Orthodox tradition, will be my own, and while I believe in their truth, I cannot naively claim that any person I cite or appeal to would agree with everything I say. This is, however, simply what it means to creatively “move forward” in dialogue with the past or thinkers of the present, and that is what I mean to do. What I am presenting is my own foolishness, my own fantasy, and I can only hope other seekers find wisdom in it.

THE (Possible) WAYS OF FUTURE ORTHODOX THEOLOGY

A truth recognized by the great thinkers of 19th and 20st century Orthodoxy, especially the Russian emigres, was that the concepts and questions of ecclesiology did not have clear or “given” answers in prior Church history. “It is nearly impossible to begin with a precise definition of the Church, for indeed, there are none that would be able to make claim to a recognized doctrinal authority,”[5] stated Fr. Georges Florovsky, and Fr. Sergei Bulgakov also insisted, “it is… impossible to find in Patristic literature any special doctrine concerning the Church.”[6] Prior to the late scholastic period, and especially in the time of the Seven Ecumenical Councils, one could find patristics such as Denys or Maximus writing on the Church from a cultic and theurgic perspective, bishops creating concepts of hierarchal authority, or councils local or imperial variously evidencing or forcefully enforcing unity, but what one could not find was any systematic ecclesiology nor any always-the-same hierarchal institution or magisterium. Furthermore, the very nature of truth as such was recognized as being incompatible with any submission of truth to mechanism as its establishment, justification or guarantee.

A consequence of the above insights, not easily accepted by many Orthodox but still logically unavoidable, is that not only must the institutional myths of unchanging infallibility be discarded, but that the invocation of reception as something which, based on an arbitrary appeal to mechanism at this or that point of history, can rule an issue as exhaustively settled and admitting no further or dissenting thought (that is, binding conscience), must also be discarded. In Bulgakov for example we find this truth exemplified in how he approached the history of dogma in his Greater Trilogy, as well as in his affirmation that “the life of the Church is a continuous revelation… [and] the very possibility of continuing revelation presupposes the incompleteness of revelation in history and, therefore, a corresponding incompleteness of dogmatic theology.”[7]

“The question of an exterior organ of infallibility in the Church by its very form faces us with heresy,”[8] declared Bulgakov. This heresy is idolatry, the reduction of the Truth to historical and finite formulae, practices, and institutional organs of power, devaluing not only the divine but the human as well. The human person, having reduced the infinite to the finite, rejects the transcendent horizon of Truth which would beckon him to continually examine and renew his faith and understanding of Truth, and so personal life and freedom are in principle denied, in practice to be nullified at whatever juncture a tradition believes bare authority trumps them. Following then from this negative assessment of history regarding the reality of any given systematic ecclesiology, and the necessary rejection of reducing truth and life to institutional mechanism, Orthodox figures recognized the need for a creative articulation of this unity of truth and life as the “Church.” Fr. Pavel Florensky’s remarks are representative of the vision and concerns of pretty much every consequential Orthodox thinker in our previous two centuries:

How then can this “fulness” of Divine life be packed into a narrow coffin of logical definition? It would be ridiculous to think that this impossibility disproves in any way the existence of ecclesiality. On the contrary, its existence is rather proved by this impossibility… Where there is no spiritual life, something external must exist as an assurance of ecclesiality… In the final analysis, in both cases what is decisive is a concept, an ecclesiastical-juridical concept for Catholics and an ecclesiastical-scientific concept for Protestants. But by becoming the supreme criterion, a concept makes all manifestation of life unnecessary… The indefinability of Orthodox ecclesiality, I repeat, is the best proof of its vitality… the life of the Church is assimilated and known only through life… If one must nevertheless apply concepts to the life of the Church, the most appropriate concepts would be not juridical and archaeological ones but biological and aesthetic ones. What is ecclesiality? It is a new life, life in the Spirit. What is the criterion of the rightness of this life? Beauty.[9]

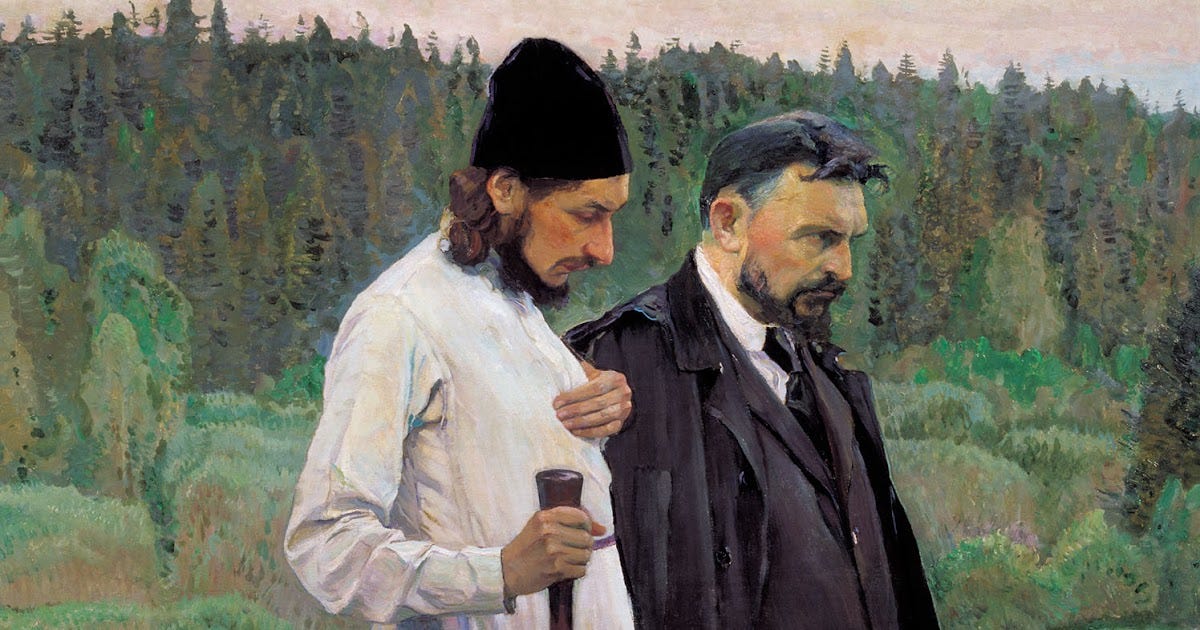

Putting aside the unfortunate polemics characteristic of Fr. Pavel’s time, we ascertain here an understanding of the unity of truth and life which is impossible to reduce to any institution or mechanism. Furthermore, claiming that the truth of the Church is found in life rather than concepts and that its criterion is beauty, beauty understood as the manifestation of being’s wholeness from beyond the limits of this antinomically shaped world, is essentially to say the only criterion and access to truth is the manifestation of truth itself. The “Russian school” then, taking up the linguistic and socio-philosophical concept of the Slavophile Alexei Khomiakov, with the ideas of Godmanhood and creation/history as a rational unity flowing forth as Sophia and returning to God as All-Unity from Vladimir Soloviev, undertook the creative task of articulating an ecclesiology of Sobornost.

Sobornost, being the Russian translation of “catholic,” for Russian theologians and philosophers connoted and included the ideas of catholicity, conciliarity, ecclesiality, ecumenicity, and harmonious unanimity.[10] Understood along with the theological ideas of Godmanhood, conceiving of the world as God in the mode of finitude becoming God as containing all in eternally actualized Triunity, and of pan-humanity, summarized in the conviction that “vindication of God is to be found in man himself and in the pathways of human existence,”[11] the ecclesiology of Sobornost at its core was a “theanthropology” and Christian humanist vision. Using Paul Valliere’s understanding of “Sobornost” as the ideal and “sobornaia” as the phenomenological aspects of this ecclesiology, one could say that under Sobornost the Russian School understood the substance of truth as that transcendent Triune subject, even God-human subject, never reducible or isolatable to any point of history yet manifest within it, just as finitude exists as manifestation of infinity, and so compelling real growth in understanding until the eschaton when history would be found as a rational unity within this All-Unity of God. Sobornaia then signifies the phenomenologically lived reality of this truth and its ethical implications, namely that all human activity must be recognized as a source of revelation, and that development in every sphere of human life is not something merely to be critiqued and corrected from the standpoint of settled doctrine, it must be recognized as capable of correcting the Church as well. Indeed, the Church rightly understood is not institution at all (though institution must function as an icon of Sobornost), it is every human being, the eternal humanity and its earthly process of growth into the perfect man (Eph 4:13), and in that process as in its end the Sabbath is made for man and not the reverse (Mk 2:27).

Certainly, the above explanatory summation represents my own synthetic engagement with various thinkers of the Russian School who not only had disagreements with one another, but at differing points may have limited the logic of Sobornost to the limits of hierarchal authority or institutional boundary for this or that reason. With that qualification given, I do believe that the ideas they articulated of Sobornost, Godmanhood, pan-humanity, etc., at their core and when taken to their conclusions constitute a vision and ethos of reformist Christian humanism, whose potentials for development point clearly in the direction of religious universalism and pluralism. In fact, according to Valliere, this orientation towards universalism and humanism, however imperfectly represented, was and is a key difference between the “Russian School” and the Neopatristic project, though the difference is not easy to see at first:

…the Neopatristic position is not merely that theology should follow the lead of the fathers, but that in the works of the fathers one finds a singular and comprehensive tradition which provides the pattern for Orthodox theologizing. Such an assumption is necessary if Neopatristic theology is to acquire shape, since patristic literature as a historical phenomenon is an extremely variegated corpus of texts comprising a wide range of opinions.[12]

Now to be clear, the above characterization should not be understood crudely. Fr. Georges Florovsky, the most important figure in establishing the Neopatristic project as the ideology of Orthodoxy, did not believe in a naïve “consensus partum” and even disliked the term.[13] “Neopatristic synthesis” was not meant to be a simple repeating of the fathers, instead it was supposed to be an acquiring of their “mind,” that is, their way of doing theology, assimilated to through (a) immersion in ecclesial life and (b) schooling in “Christian Hellenism,” so as to move forward with the patristic legacy in the present. Florovsky was even open to Orthodoxy learning from and dialoguing with the Western scholastic tradition as a continuation of Christian Hellenism,[14] however, this particular openness betrayed the nature of his project’s closed-mindedness. For Fr. Georges, not only German Idealism but Christian Neoplatonism were unacceptable and not to be granted part in “Christian Hellenism” except as heresies to help negatively ground his ideological picture of Orthodoxy. Christian Hellenism was understood by him as not only the impossibility of separating philosophy from religion, but as the legacy of a certain “synthesis” of Greek philosophy by “the fathers,” specifically a reading of Nicaea as definitively alienating the world from God’s life and establishing the primacy of will/freedom between God and world, such that God could have chosen not to create and the world could either, by grace, attain a theosis unnatural to it or, alternatively, subject itself to eternal disintegration of being in Hell.[15]

This ideological project, in hindsight, is clearly a violent truncation of the diversity of patristic viewpoints, not to mention that it enforces a misreading of figures it claims as authoritative but who in no way fit into its limits of “Christian” Hellenism (e.g., Gregory the Theologian, Gregory of Nyssa, Denys the Areopagite, Maximus the Confessor, etc.),[16] all in service of a consciously ideological drive to quash contemporary rivals to its vision while constituting Orthodoxy as a partner in the settlement between the Nouvelle Theologie and Thomism. This alone demonstrates the project as having an implicit affinity for authoritarianism, as such a limited picture of tradition rests on an absolutization of its limited reading as simply true and all divergent witness as wrong in principle, but its authoritarianism is especially clear in its misuse of Origen. For Florovsky’s project the condemnation of Origen was a kind of key to “Christian Hellenism,” as the (supposed) views of Origen (taken as representing Bulgakov’s theology which Florovsky never understood) were its antithesis,[17] and so the unconscionable authoritarianism represented by the condemnation and institutionalized centuries long slander of Origen was for Florovsky a justified and non-negotiable authority.

My goal here however is not to lambast Fr. Georges or any other Neopatristic theologian, as I still find many things valuable in their work,[18] but these things I also find to be at their most valuable when one traces them back to the Russian School, both to the ideas it produced and that general intuition and ethos undergirding their ideas as its expressions. It is this legacy that I think is most “fecund” and promising as the ground for future theology, and to my mind the ethos of the Russian School, granting all its diversity, has its greatest modern continuator in David Bentley Hart. The Russian School’s articulations of “Sobornost” or “Ecclesiality” as the Spirit vivifying a living tradition towards greater realization of Godmanhood, is what Hart elucidates clearly as the “final intentional horizon” and “intrinsic final causality of the tradition’s rational unity.”[19] Like the Russian School again, including such different thinkers as Berdyaev and Bulgakov, Hart understands the nature of truth and tradition as a manifestation of the nature of person/rational spirit, abiding by no other law than the necessary rational tautology that truth, conscience and beauty are their own standard, and so denying the vicious tautology of externalist authority. In short, if Orthodoxy today faces the challenge of examining its current Neopatristic ideological structure and reorienting itself to move forward with a different legacy in constructing its future, Hart is both showing the way there and has already arrived.

The above said, David Bentley Hart not only continues the Russian School’s legacy, his thought on Godmanhood and the nature of tradition provide immense potential for the development of a real and radical Christian religious pluralism, not as compromise but as a new integral development of Christian tradition. Hart is willing to admit explicitly, unlike many of even the most daring of past theologians who were more reserved, that dogmatic history includes not only positive development but also negations, that is, real change. Furthermore, he argues not only that dogmatic formulae and the current statuses of dogmatic belief in general are only signposts towards a transcendent horizon of intentionality whose antecedent finality, never exhausted in history but recapitulating it into a rational unity, must be recognized as the same for all historical manifestations of the human orientation toward the transcendent:

It is wrong, for instance, to speak of Christianity appropriating or borrowing from Platonism, or from any other school of thought, as if those other traditions were nothing but boxes filled with a variety of useful implements. Each such tradition possessed and internal rational unity of its own, from which individual parts could not be wholly separated without losing their meaning. One living tradition could not possibly successfully absorb elements of another if there were not already a more encompassing rationality to which both were already obedient. If the Christian and Platonist traditions could combine with one another and in the process disclose dimensions in each that until then had been only latent or unformed… it can only be because the rational unity that each possessed already profoundly coincided with the rational unity possessed by the other. And this is to say that in some sense they must have shared a common guiding finality. Christianity did not plunder Platonism. Christian and Platonist traditions converged, because both were summoned by and aspired to a horizon of spiritual intimacy with the divine, one that for Christians is understood as the final realization of what was achieved in the person of Christ. Each tradition, by practicing the universal human virtue of religion, found the other along the way.[20]

Not inclusivism, which is always implicitly a colonialism and triumphalism, but pluralism is what recognizing the infinite within and as the destiny of the finite entails. A pluralism, one must notice, that grounds a strong religious humanism capable of going beyond institution to find human being and life as such as the essence of “ecclesia,” or rather, as the ecclesia in becoming. In what follows, then, I mean to argue from the rationality of the Christian tradition of deification for the necessary rationality of a radical Christian theological/metaphysical pluralism, one which in no way compromises the Trinitarian and Christological dogmas of Christianity (and specifically Eastern Orthodoxy) nor the absolute significance of Jesus Christ, but finds pluralism to be an outworking of their integral rationality.

(To be Continued…)

[1] Timothy Troutner, “Crisis of a House Divided,” A Wild Logos, April 24, 2025.

.

[2] Andrew Kuiper, “The Crisis of a House (Still) Divided,” Naucratic Expeditions, June 11, 2025.

.

[3] The articles are collected here in David Armstrong & Jordan Daniel Wood, “Reform Catholicism: A Digest,” A Perennial Digression, June 1, 2025.

.

[4] Nikolai Berdyaev, “Does There Exist Freedom of Thought and Conscience in Orthodoxy?,” Journal Put’, feb./apr. 1939, No. 59. Accessible at https://www.nicholasberdyaev.com/articles/articles-1930-1939.

[5] Fr. Georges Florovsky, The Body of the Living Christ. Translated by Robert M. Arida. (Boston, MASS: The Wheel Library, 2018), 22.

[6] Fr. Sergei Bulgakov, The Orthodox Church. (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1988), 79.

[7] Fr. Sergei Bulgakov, “Dogma and Dogmatic Theology” first published in Living Tradition. (Paris, FRA: YMCA Press, 1937). Accessed here https://afkimel.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/bulgakov-on-dogma-and-dogmatic-theology.pdf.

[8] Bulgakov, The Orthodox Church, 60.

[9] Fr. Pavel Florensky, The Pillar and Ground of the Truth. Translated by Boris Jakim. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997), 7-8.

[10] Bulgakov, The Orthodox Church, 60-61.

[11] Nikolai Berdyaev, Self-Knowledge. Translated by Katherine Lampert. (Philmont, NY: Semantron Press, 2009), 301.

[12] Paul Valliere, Modern Russian Theology: Bukharev, Soloviev, Bulgakov. (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2000), 376-377.

[13] Fr. Georges Florovsky, “On the Authority of the Fathers” in The Patristic Witness of Georges Florovsky. Edited by Brandon Gallaher and Paul Ladouceur. (New York, NY: T&T Clark, 2019), 238. I should note that this project by my late professor Dr. Ladouceur, along with many other esteemed scholars, is the definitive collection of Florovsky’s key writings.

[14] See the late Fr. Matthew Baker’s “Neopatristic Synthesis and Ecumenism: Towards the 'Reintegration' of Christian Tradition” published in Eastern Orthodox Encounters of Identity and Otherness: Values, Self-Reflection, Dialogue. Edited by Andrii Krawchuk and Thomas Bremer. (New York, NY: Palgrave-MacMillan, 2014), 235-260, for the best explication of Florovsky’s overall project and ecumenical motives from a sympathetic angle.

[15] See Florovsky’s “Creation and Createdness,” 33-64.

[16] See for example the defense of patristic “pantheology” in David Armstrong, “Pantheology and Christianity,” A Perennial Digression, April 8, 2022.

, or Jordan Wood’s demonstration of Sts. Irenaeus, Athanasius, Gregory of Nyssa, Gregory Nazianzen, Dionysius and Maximus belief in God’s eternal and necessary creation of the world in “That Creation is Incarnation in Maximus the Confessor.” PhD Thesis. (Boston College: https://dlib.bc.edu/islandora/object/bc-ir:108259, 2018), 132-134.

[17] Paul L. Gavrilyuk, Georges Florovsky and the Russian Religious Renaissance. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2014),140-143.

[18] For example, I greatly appreciate and recognize the influence Florovsky’s concepts of “intellectual podvig” and “intellectual ascesis,” of tradition as a creative effort in which “leaps” could be made and not a slavish repeating of the past, etc., have had on me. As of now I simply find that these influences have led me back to his one-time spiritual father and longtime rival Bulgakov (though the feeling of rivalry was very much one-sided on Florovsky’s part).

[19] David Bentley Hart, Tradition and Apocalypse. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2022), 183.

[20] Hart, Tradition and Apocalypse, 185-186.

Really enjoyed reading this. Stumbling onto the Russian School through Berdyaev has been one of my greatest theological joys. I'm far too much of a novice to make sweeping claims about it, but I thoroughly appreciated reading your engagement with it here.

Very fine job. And I must say that, speaking for myself at least, I have been and continue to be profoundly influenced by the Russian School and its current restive rascal, David Hart. In fact I would say that Berdyaev has influenced me more than perhaps any “Catholic” thinker. And yet, to close the ecumenical circle, it is precisely Catholic as well to look to, say, Soloviev, as exemplar of faith and reason, as JP 2’s Fides et Ratio indicates by naming him as such. Looking forward to part 2!